This post is intended to be a brief overview of Dr. Joseph Waligore's new book on deism. I plan on having much more to say, but in this post, I try to hit some main points.

Waligore observes and constructs a number of different theological categories in his analysis to compare and contrast with the theology of deism. "Christianity" generally requires belief in orthodox Trinitarian doctrine and authority of the entire Bible (it's mainly Protestant Christianity that is being analyzed, so it would be the 66 book Protestant canon).

There is one kind of "traditional Christianity" that, for lack of better words, is neither "freethinking" nor "ecumenical" on doctrine and dogma. Even though many more than two traditions within Christianity could be invoked to serve this purpose, it's mainly Calvinism and High Church Anglicanism that serve as useful guideposts in his book. (Though other forms, like Arminianism are also analyzed.)

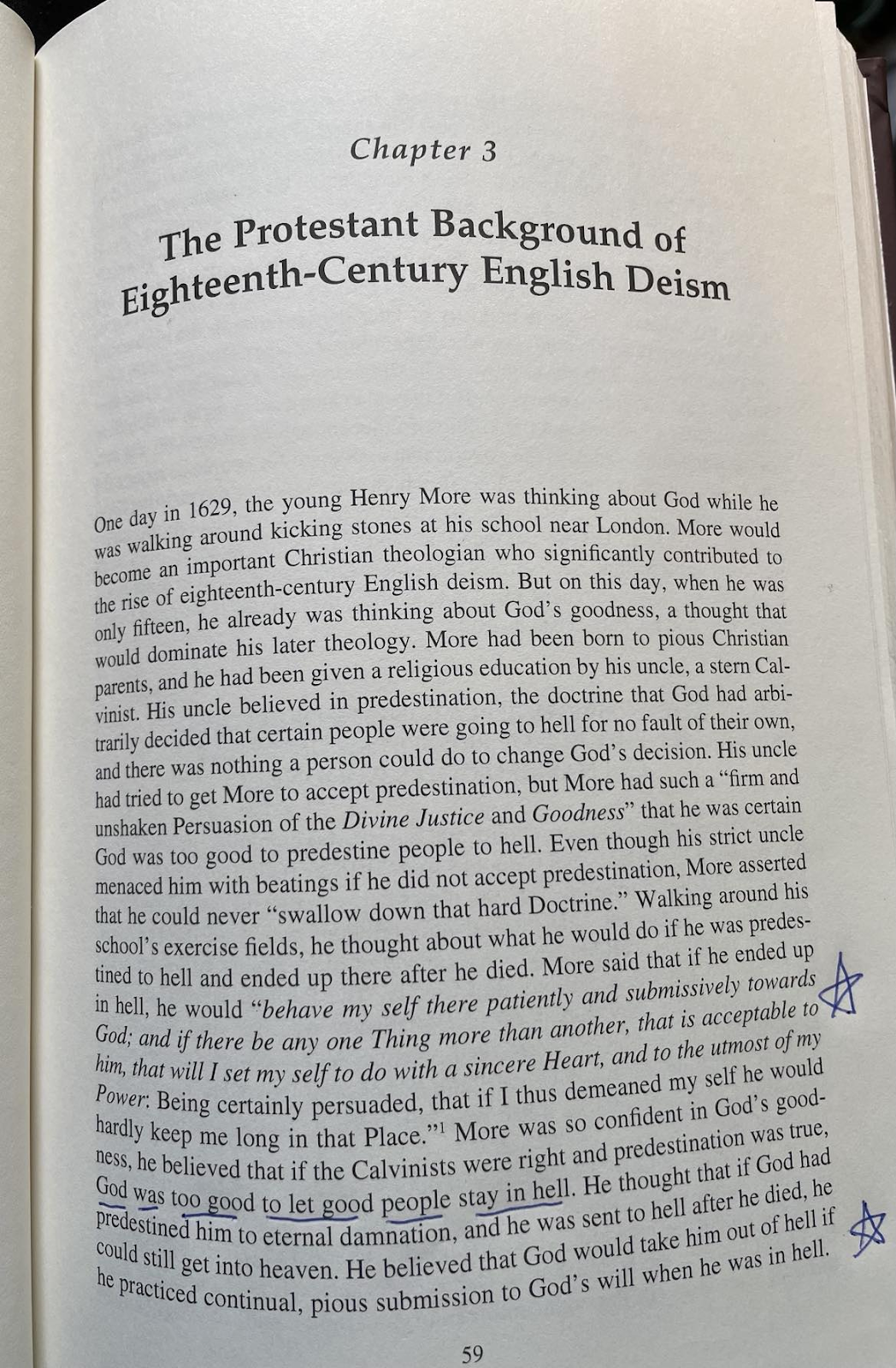

Waligore observes the voyage of (Protestant) Christianity to Deism, by noting two OTHER Christian traditions that in the 17th Century started to engage in "doctrinal freethinking" for lack of a better term. The Cambridge Platonists and the Latitudinarians (the name refers to "latitude" on matters of doctrine). Though the reason why they merit the label "Christian" is again, they tended to endorse orthodox Trinitarian doctrine and the authority of the entire Bible.

One potential point of criticism is as much as we want figures to neatly fit into different "boxes" that we construct for a better, more accurate understanding, is that people often don't neatly fit into those boxes. For instance, Samuel Clarke gets put in the "Latitudinarian" not "Unitarian" box; though arguably he could fit into either one. The boxes tend to bleed into one another.

But the pages I included in the photos on the Cambridge Platonists illustrate such freethinking (many of them seemed to flirt with some kind of modified universalism, and belief that human souls pre-existed and exercised their will prior to their physical birth, among other things). Yet, they remain "Christian" because, again, they claimed their heterodox ideas didn't contradict either the Bible or the doctrines of the Church of England.

By the time we get to the Unitarians, they lose the label "Christian" because of their disbelief in the Trinity. But Waligore stresses that they tended to have more respect for the entire Bible than the deists did.

And that sets the stage for an intense, meticulous analysis of the various forms of deism. And the chief message of this book is that while there are certain points that can be drawn to form a "deist" creed, belief in a non-intervening watchmaker God was actually a minority belief among the deists. Deism came in many varieties and most of them believed in a Providential God. And for those who did believe in Providence, they much more freely "picked and chose" what parts of the Bible they thought legitimately revealed and which parts they thought not.

Waligore also stresses that while the deists in general venerated man's reason as a discerner of truth, the notion that God was ultimately benevolent was the primary lens through which they viewed theology. Anything part of traditional Christianity or any other creed that they deemed made God look less than perfectly benevolent was cast aside.